di Antonio Bordoni.

Obbligatori sugli aerei che battono bandiera a stelle e strisce dal 2004, ancora facoltativi altrove: è così che può essere sintetizzata la situazione circa l’obbligo di trasportare a bordo dei velivoli di linea un defibrillatore che potrebbe salvare la vita a passeggeri e membri di equipaggio.

Il condizionale è d’obbligo in quanto il defibrillatore ha successo solo se la crisi è riconducibile a un ritmo defibrillabile efficacemente ma, dicono gli specialisti, nulla da fare se l’infartuato ha un blocco atrio ventricolare. (1)

L’argomento è tornato alla ribalta nel giugno dello scorso anno allorchè a bordo di un aereo in volo fra Londra e Los Angeles è deceduta l’attrice Carrie Fisher, la principessa Leila di Star Wars, ma ne riparliamo oggi a seguito del triste caso di una bambina di due anni morta a bordo di un aereo Alitalia in volo fra Beirut e Roma. (2)

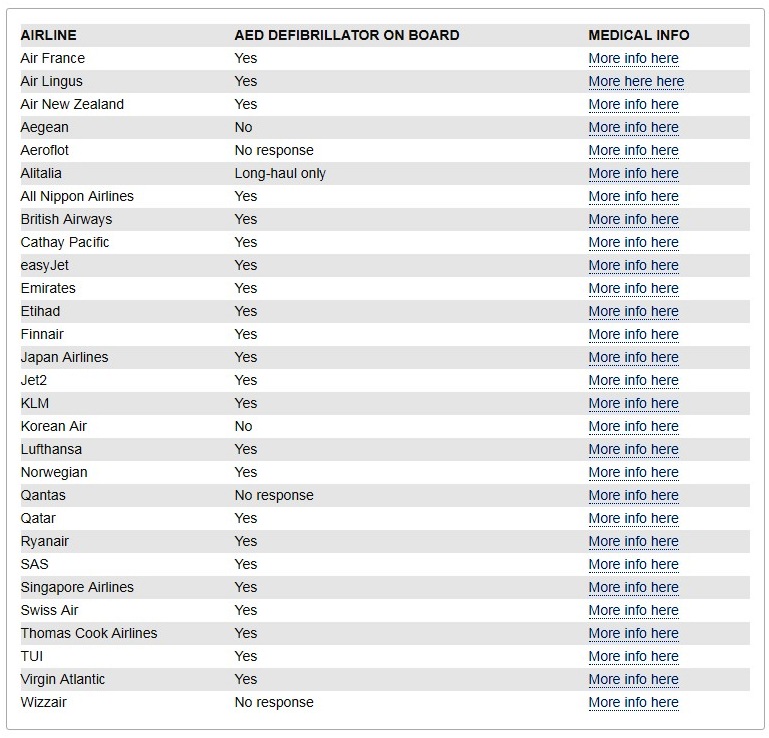

Tabella tratta da: https://www.aph.com/community/holidays/airlines-heart-defibrillators-flights-uk/

Quest’ultimo caso è del tutto particolare dal momento che, da quanto trapelato, la bambina aveva una patologia in corso (iperossaluria), viaggiava con la maschera ad ossigeno ed era diretta al Bambin Gesù di Roma con relativo permesso sanitario per le cure. Tuttavia dal momento che i casi di problemi cardiaci non sono affatto infrequenti a bordo di aerei, ritorniamo sull’argomento.

Quest’ultimo caso è del tutto particolare dal momento che, da quanto trapelato, la bambina aveva una patologia in corso (iperossaluria), viaggiava con la maschera ad ossigeno ed era diretta al Bambin Gesù di Roma con relativo permesso sanitario per le cure. Tuttavia dal momento che i casi di problemi cardiaci non sono affatto infrequenti a bordo di aerei, ritorniamo sull’argomento.

La defibrillazione e la rianimazione cardiopolmonare hanno un effetto temporaneo sulla crisi per cui è imperativo scendere di quota ed atterrare al più presto facendo trovare mezzi sanitari pronti all’aeroporto.

Fra le raccomandazioni avanzate al congresso Euroanaesthesia tenutosi a Colonia nel giugno 2017 sotto gli auspici della Società Tedesca di Medicina Aerospaziale è stato avanzato che gli aerei abbiano a bordo un defibrillatore esterno automatico in grado di registrare un ECG, inoltre viene raccomandato che durante l’annuncio di sicurezza che viene fatto prima del decollo vengano specificate quali attrezzature di emergenza siano disponibili su quel determinato volo.

La cosa fondamentale comunque che ancora manca è che l’ICAO renda obbligatoria questa strumentazione di emergenza a bordo per tutti gli aerei di linea. Attualmente infatti navighiamo ancora nel campo delle raccomandazioni:

La cosa fondamentale comunque che ancora manca è che l’ICAO renda obbligatoria questa strumentazione di emergenza a bordo per tutti gli aerei di linea. Attualmente infatti navighiamo ancora nel campo delle raccomandazioni:

Dall’Annesso 6 dell’ICAO:

Sulla base delle prove disponibili limitate, solo un numero molto limitato di passeggeri può beneficiare del trasporto di defibrillatori automatici esterni (AED) sugli aerei. Tuttavia, molti operatori li portano perché offrono l’unico trattamento efficace per la

fibrillazione cardiaca. La probabilità di utilizzo, e quindi di potenziale beneficio per un passeggero, è maggiore negli aeromobili che trasportano un gran numero di passeggeri, per lunghezze del settore di lunga durata. Il trasporto di DAE dovrebbe essere determinato dagli operatori sulla base di una valutazione del rischio che tenga conto delle esigenze particolari dell’operazione.

Così come ancora siamo nelle raccomandazioni nel caso del bollettino dell’EASA emesso il 30 gennaio 2018 di cui pubblichiamo il testo integrale in allegato.

Quindi rimane solo la Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Questa agenzia fin dall’aprile 2001 ha emesso una norma obbligatoria che prevede che gli aeromobili che abbiano un carico pagante superiore ai 3400 Kg e volino con un attendente di cabina devono avere un defibrillatore automatico esterno (AED) e un kit di emergenza (EMK). La norma vale per le aerolinee statunitensi è valida su tutti i voli domestici e internazionali ed è entrata in vigore dopo 3 anni dalla sua pubblicazione.

Allegato:

EASA SIB No.: 2018-03

Safety Information Bulletin Operations

SIB No.: 2018-03

Issued: 30 January 2018

Subject: Carriage and use of Automatic External Defibrillators

Commission Regulation (EU) 965/2012 of 5 October 2012, hereafter referred to as the Air Operations Regulation.

ICAO Annex 6 Part I, Operation of Aircraft – International Commercial Air Transport – Aeroplanes.

Applicability:

Aeroplane Operators conducting Commercial Air Transport (CAT) operations.

Description:

The carriage of automated external defibrillators (AED) has been debated at length in the aviation community. EASA has received and continues to receive regularly questions on the matter.

Technological developments of the devices available on the market and changing passenger demographics are further reasons to re-consider the topic. A survey conducted among European Competent Authorities also showed that many large CAT operators have chosen to carry AEDs as a normal practice in their operations and train their crews on that.

The objective of this SIB is to provide recommendations to operators on the carriage and use of such devices.

Current regulatory situation in Commercial Air Transport:

ICAO annex 6 Part I, namely attachment B with reference to 6.6.2 on medical supplies, recommends operators to determine through a risk assessment the need to carry an AED on aeroplanes with more than 100 passengers flying on sectors of more than two hours.

EASA, namely AMC1 CAT.IDE.A.225 on emergency medical kits (EMK), recommends operators to determine through a risk assessment the need to carry an AED in the EMK on aeroplanes with a maximum operational passenger seating configuration (MOPSC) of more than 30 passengers flying more than 60 minutes at normal cruising speed from a suitable aerodrome.

The FAA, namely FAR 121.803 (c)(4) on emergency medical equipment, requires AEDs on aeroplanes where a cabin crew member is required and with a maximum payload of more than 7 500 pounds (approximately 30 passengers or more).

Rationale to carry an AED:

As a therapeutic tool, defibrillators are used to treat ventricular fibrillation (VF), the most common form of treatable cardiac arrest. When a VF occurs, the survival rate is good if the electrical shock

Recommendation(s):

EASA recommends CAT operators to carry an AED on aeroplanes having a MOPSC of 30 or more where at least one cabin crew member is required.

EASA recommends CAT operators to consider the following aspects in the implementation of CAT.IDE.A.225 and the associated AMC1:

Risk Assessment Criteria:

The need to carry an AED should be assessed primarily against passenger benefit. However, when an AED is carried, its use should be also considered in the event of crew incapacitation.

Operators should consider at least the following elements in the risk assessment:

The seating capacity of the aeroplane in use;

The passenger demographics;

The total number of passengers transported per year;

Duration of the flight and route structure, although the distinction between long-haul and short-haul routes is less relevant as the time factor in getting to an airport becomes negligible in a situation where minutes are vital. However, it is relevant to consider the availability of airports where medical assistance is available after the use of an AED in flight;

When available, guidance from aircraft manufacturers for carriage and use of an AED on their respective aircraft types.

Types of AED:

Fully automated AEDs, with no manual functions, are recommended as they are the easiest and safest to use, requiring minimal training. Security risks, possible with other types of AEDs, are also excluded for this type of device. An AED may be also a function of a medical device with other functionalities; in this case however, it is up to the operator to consider in the risk assessment any differences and additional needs for its carriage and use. The use of AEDs is recommended in conjunction with other resuscitation tools present in the EMK.

Maintenance:

The operator carrying an AED should ensure the serviceability of the device especially with regard to the batteries. Periodical checks in accordance with instructions of the device manufacturer should be included in the maintenance programme.

Crew Training:

The use of AEDs should be part of the initial and recurrent training of cabin crew. The training material should be developed by or in cooperation with medical personnel. The amount of training required is considered to constitute a small add on to the existing First Aid training syllabi.

Contact(s):

For further information contact the EASA Safety Information Section, Certification Directorate. E-mail: ADs@easa.europa.eu.

(1) Tratto da: R.it Medicina, articolo datato 8 giugno 2017 a firma di Elvira Naselli

(2) La tabella è stata da noi ripresa dal sito APH Parking & Hotels, è datata 22 maggio 2018 e si riferisce ad un survey fatto da quella testata per voli in uscita dal Regno Unito. Oltre a questa limitazione è da notare che andando nella sezione “More info here” si rimanda al sito istituzionale della compagnia aerea ove sono riportate ulteriori precisazioni e limitazioni.

Tratto da www.aviation-industry-news.com